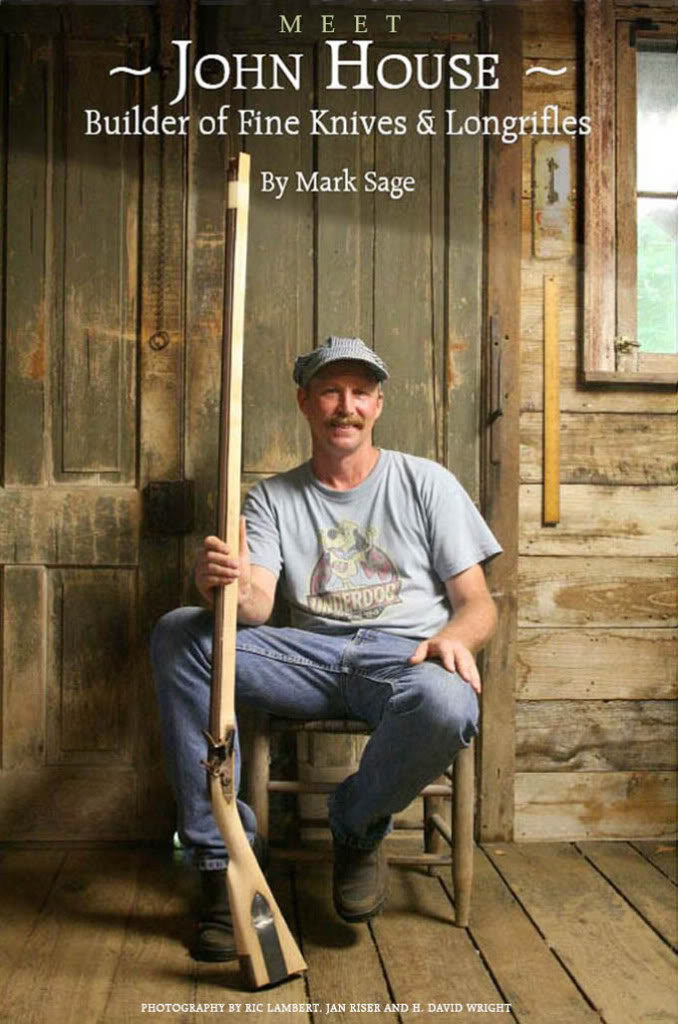

Meet John House, Builder of Fine Knives and Longrifles . . . By Mark Sage

Meet John House, Builder of Fine Knives and Longrifles . . . By Mark Sage

Photography by Ric Lambert, Jan Riser, and H. David Wright

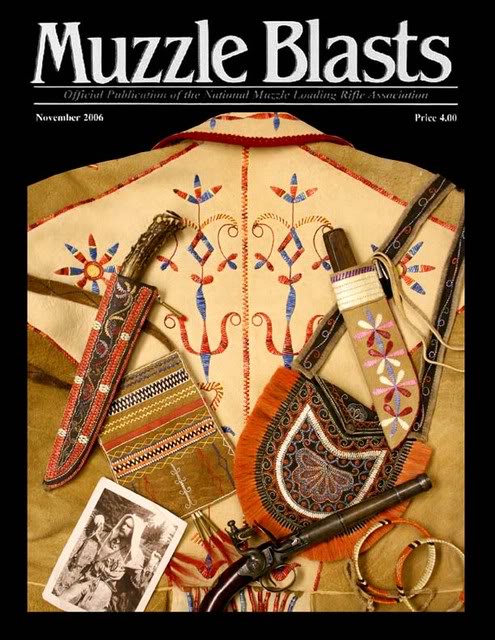

Reprinted by permission of the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association/ Muzzle Blasts magazine, March 2009. For information on the NMLRA and other black powder topics please visit the website at www.nmlra.org

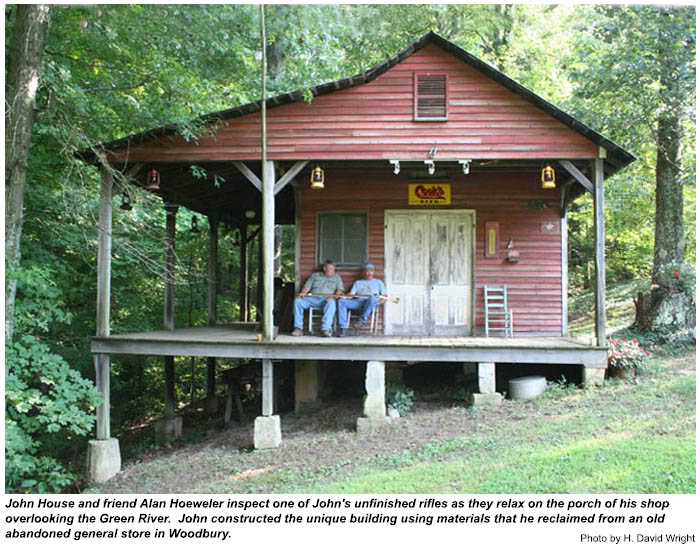

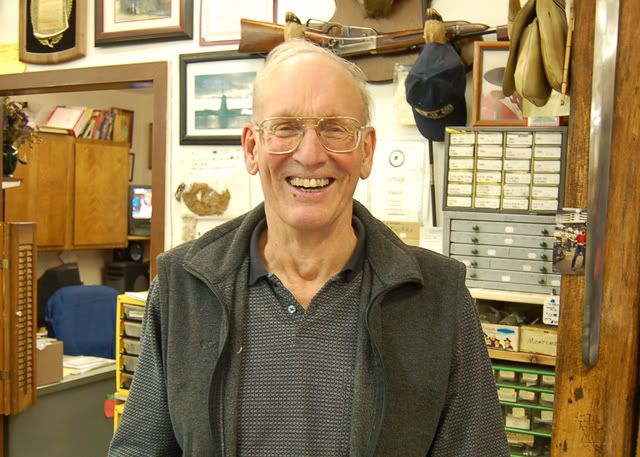

In Woodbury, Kentucky, near the Green River, is a very neat and efficient shop, reconstructed from an old general store that John House frequented when he was a boy.

It was a sentimental restoration project for John and he did 98% of the work himself with very few modern tools and even less money. John dismantled the old store piece by piece, found another similar building to help make up for some of the rotten wood and restored the relic from his early childhood that held so many pleasant memories for him.

The final result is a charming, well-built structure that is neither shiny nor pretentious – sporting the old patina on the siding and exuding an earlier era in Kentucky’s history. This resurrected building is a strong and stunning reflection of a man possessing considerable artistic talent, attention to detail and a gifted ability to meld wood and metal craft into a thing of beauty and functionality, while at the same time coaxing the past into sharp and harmonious focus. It is this commitment to patience, solid construction methods and historic realism that guides everything he does—whether it be a hand forged knife or a fine longrifle or even a willow back chair.

Yes, John is related to Hershel and Frank House. He is the youngest male sibling in the family and the three of them (they are close-knit) form a trinity of talent that have turned out many knives, firearms and accoutrements of exceptional quality and beauty.

Yes, John is related to Hershel and Frank House. He is the youngest male sibling in the family and the three of them (they are close-knit) form a trinity of talent that have turned out many knives, firearms and accoutrements of exceptional quality and beauty.

We should not be surprised. Their father was a hard working man and a boilermaker for 42 years, providing a good work ethic and example for the family. The real stream of artistic talent, however, flows through their mother Coweta’s lineage. She is a musician and professional song writer that has marketed her music to people like Faron Young, Bobby Vinton and LeAnne Rhymes. John’s grandfather, on his mother’s side, Hershel Finney was an iron worker/riveter with talent also. He made beautiful willow furniture, wooden boxes and furniture, providing income during the depression. John also is an accomplished musician, playing guitar (mostly bass) and leading with his vocals. John doesn’t compose like his mother. He calls himself a “clean up writer,” meaning he likes to help refine the lyrics once the song has been written. Presently, he is working on a 14 song CD.

Hershel’s and Frank’s work with longrifles and knives are legendary, but John has emerged as very fine bladesmith and gunsmith with his own distinctive style and flavor. The pictures accompanying this article show a few examples. Here is his story.

John House was born in Woodbury, Kentucky in 1961. Raised in an old lock house on the Green River, John describes his childhood as idyllic with Hershel being a strong roll model and mentor for both him and Frank. John explains:

“Hershel spent a lot of time with us when he came back from the Marines. Though he was twenty years my senior (Frank is a little older than me) he would take us down to the river every day he could and teach us to both fish and swim. We would also go camping. Hershel would make us little knives and things and we grew up watching him work—it’s amazing what you can pick up as a kid by accident. As teenagers, Frank and I would go out there a lot, skipping school often, working on the lathe, making knives and beating and banging on the forge. Those were great times for us. Our skipping got to be such a problem that when the school principal was contacted all he could comment was: ‘I’m not really worried about them going out there and learning all that stuff because they sure as h*ll aren’t learning anything here!’”

So John House learned, first hand, the fundamentals of wood and metal work under Hershel’s tutelage, but did not step out as a gun and knife builder till the late 1980’s.

John enumerates: “I remember back in the late eighties I hadn’t done much art or knife work and I lost my full-time job. I hung out at Hershel’s a lot and told him I didn’t know what I was going to do. Hershel told me he would show me and I watched and worked with him about four or five days. Then, I just sort of fired up the forge and took off. I have learned much since then, but I needed a push to get me going and so I started building knives.”

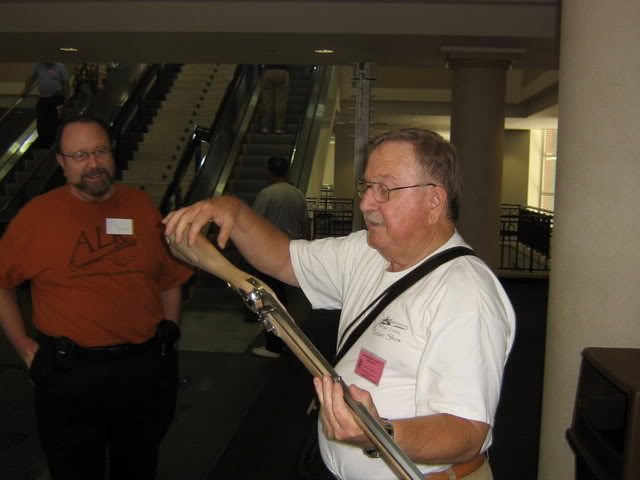

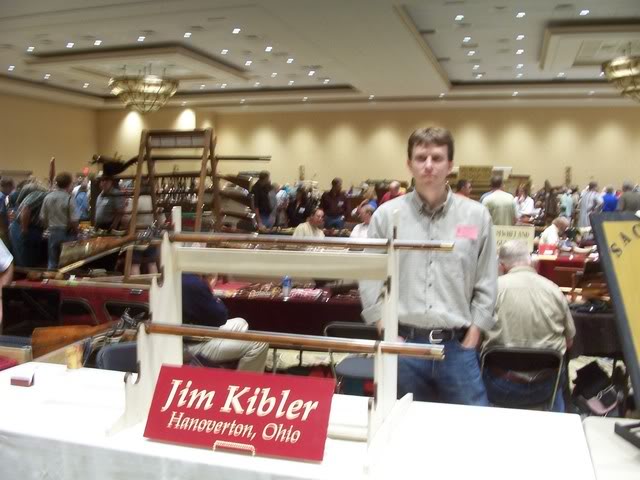

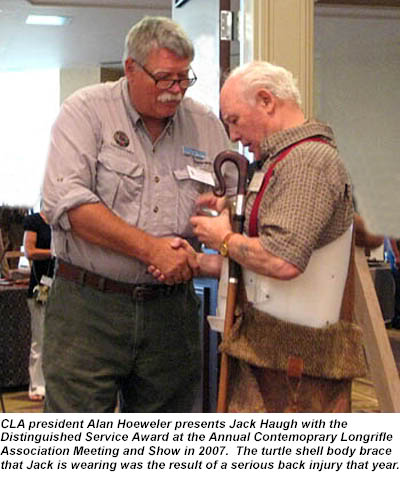

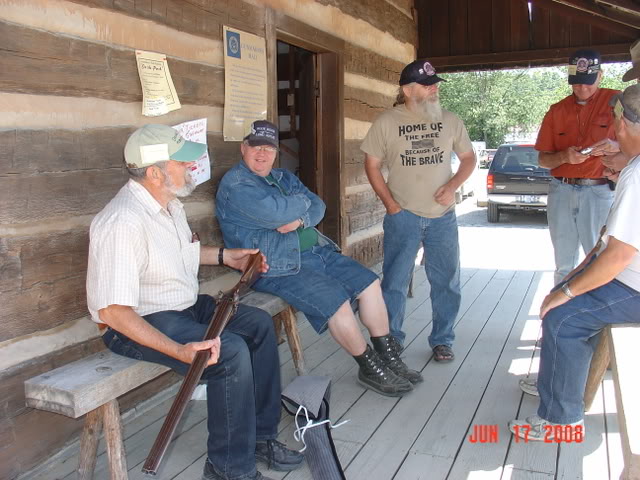

These days, John and Hershel conduct gun and knife building seminars together and freely share their knowledge, skill, and expertise. This summer the three brothers are conducting their first gunmaking workshop together at Hershel’s shop in Woodbury. John says he has made many great friends along the way.

But what about John’s longrifles? In addition to Hershel’s influence, Frank played a significant part in his development as a gun builder. He says: “I built my first rifle with Frank in his shop. Frank at that time was a journeymen boilermaker and a great welder, but had decided to go into gunsmithing on his own and had a small shop in Woodbury. At the time, I was making willow furniture and one day he said to me, ‘Look, I know you have the eye to do this!’ So, I started working with Frank and we built a brass mounted, walnut stocked, Virginia rifle. The next gun we built was an early, iron mounted, 62 caliber, long-barreled, curly maple stocked beauty. I nicknamed it Summertime, because it took all of one summer to build. I found out later that old Summertime went out to California and won a state championship. I was a real proud of that.”

But what about John’s longrifles? In addition to Hershel’s influence, Frank played a significant part in his development as a gun builder. He says: “I built my first rifle with Frank in his shop. Frank at that time was a journeymen boilermaker and a great welder, but had decided to go into gunsmithing on his own and had a small shop in Woodbury. At the time, I was making willow furniture and one day he said to me, ‘Look, I know you have the eye to do this!’ So, I started working with Frank and we built a brass mounted, walnut stocked, Virginia rifle. The next gun we built was an early, iron mounted, 62 caliber, long-barreled, curly maple stocked beauty. I nicknamed it Summertime, because it took all of one summer to build. I found out later that old Summertime went out to California and won a state championship. I was a real proud of that.”

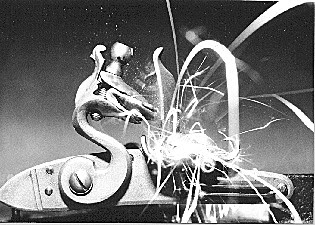

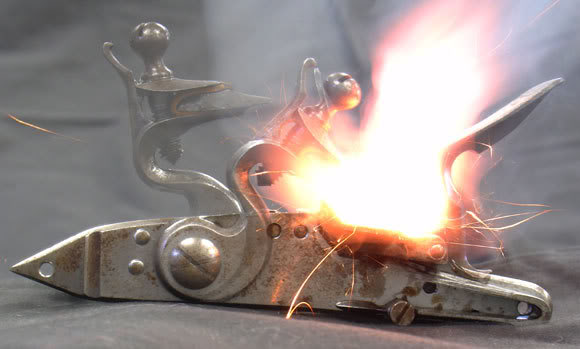

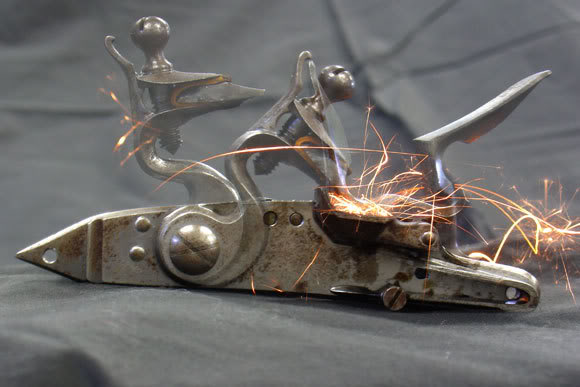

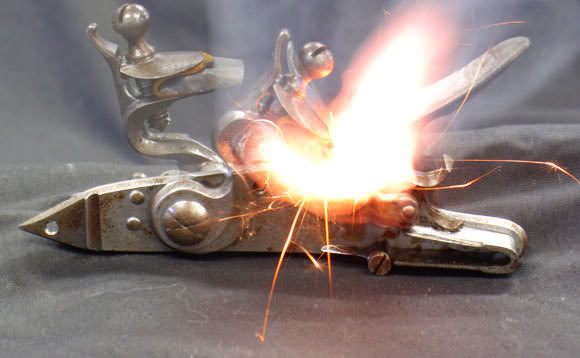

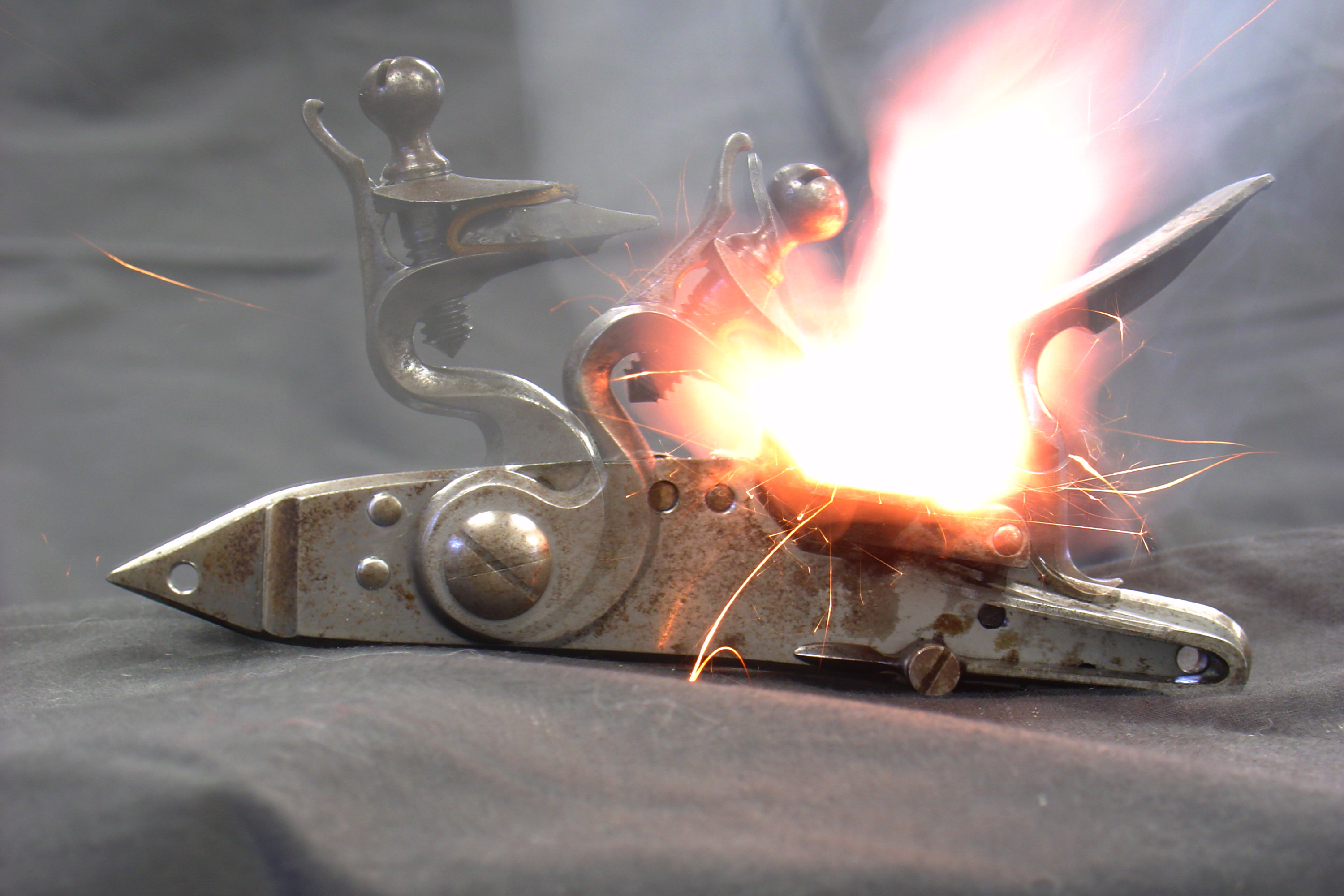

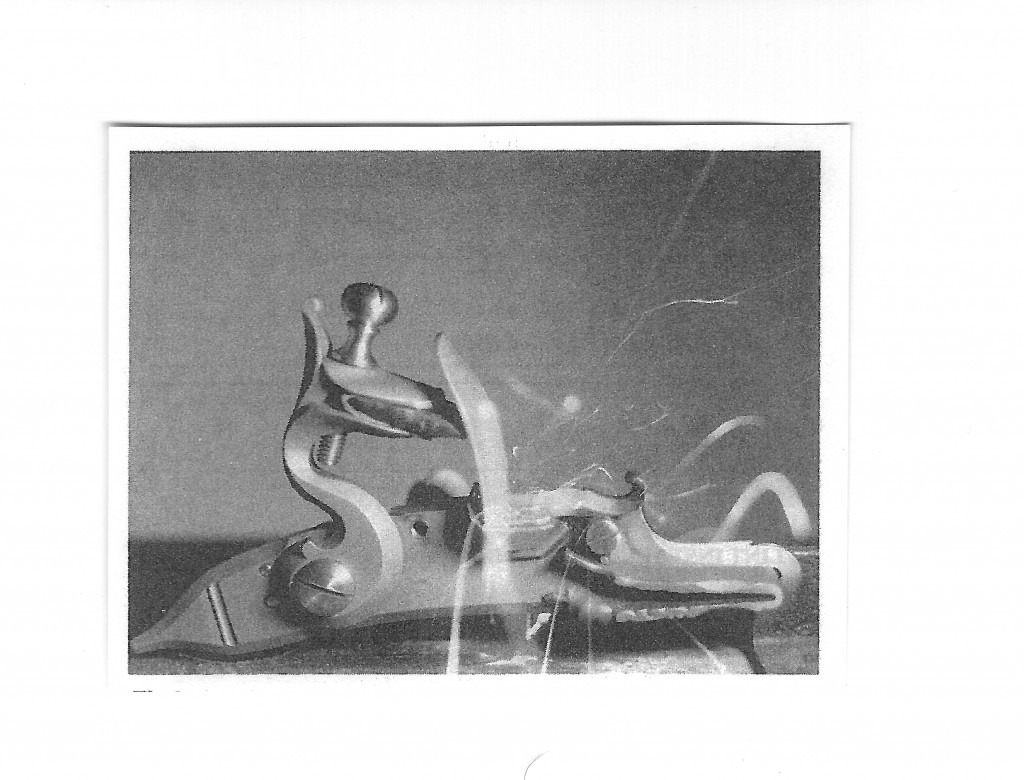

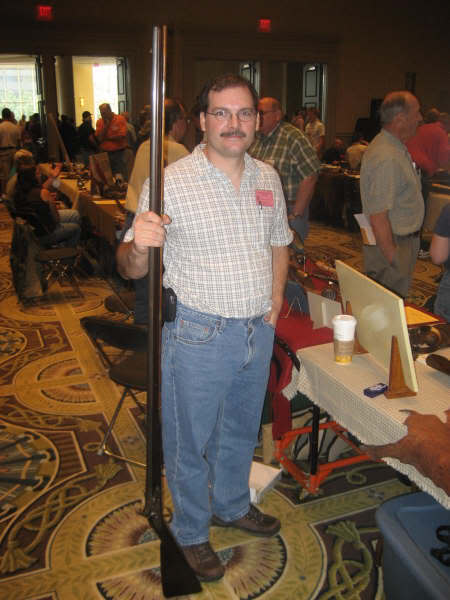

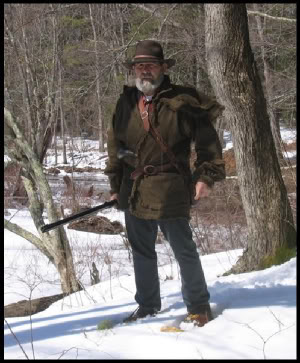

Although John likes to build early American flintlock rifles, his favorite style is the later period, flintlock mountain rifle.

Although John likes to build early American flintlock rifles, his favorite style is the later period, flintlock mountain rifle.

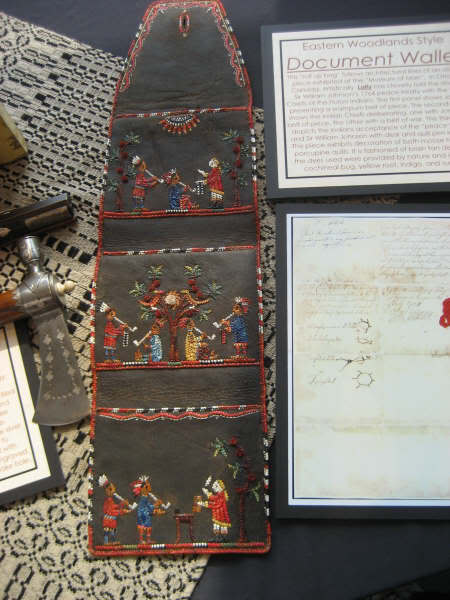

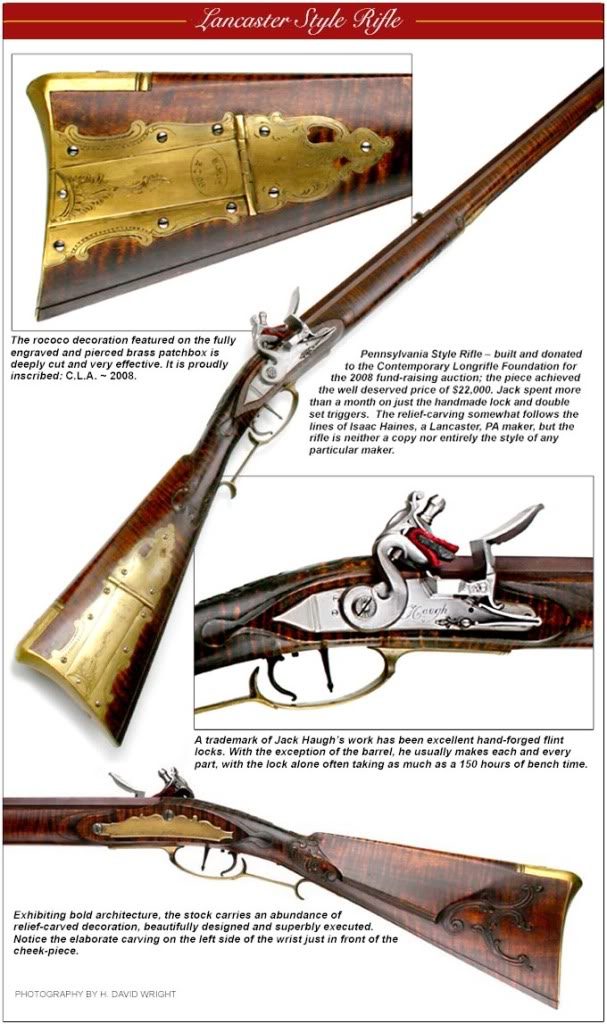

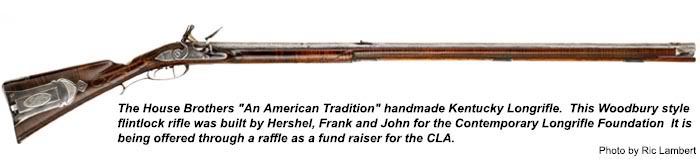

Recently, the House brothers teamed up to build an exquisite Kentucky longrifle completely from scratch—lock, stock and barrel. This rifle is being raffled as a fundraiser titled “An American Tradition” for the Contemporary Longrifle Foundation. The Foundation’s purpose is to raise funds to promote the art and history of the Contemporary Kentucky Longrifle and related arts through educational publications, museum exhibits, and grants; and to promote contemporary artists of the Longrifle Culture. You can read about this remarkable project at the CLA’s web sites: www.longrifle.ws andwww.housebrothersproject.com and view photos of this superb longrifle and the three of them at work on this gun, stage by stage. For John House, this was an especially meaningful project on a number of levels. He says: “It was really special to me and an honor to get to build this rifle with my brothers. It makes me awful proud and we always seem to have a lot of fun when we work together.”

You can read about this remarkable project at the CLA’s web sites: www.longrifle.ws andwww.housebrothersproject.com and view photos of this superb longrifle and the three of them at work on this gun, stage by stage. For John House, this was an especially meaningful project on a number of levels. He says: “It was really special to me and an honor to get to build this rifle with my brothers. It makes me awful proud and we always seem to have a lot of fun when we work together.”

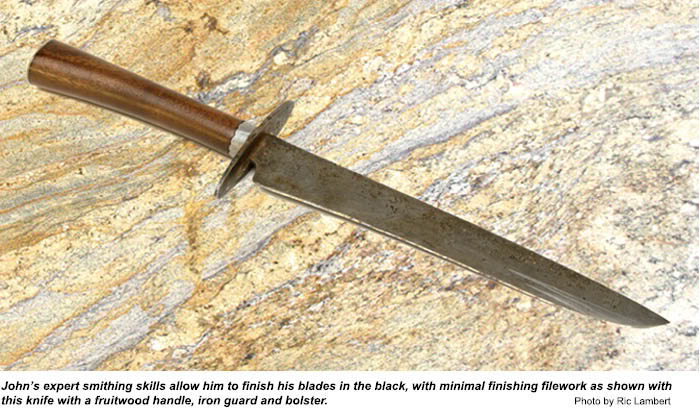

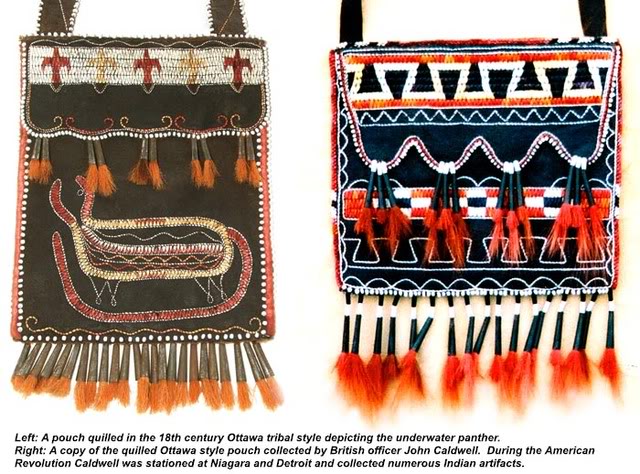

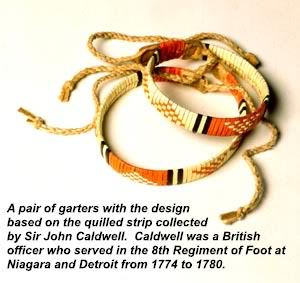

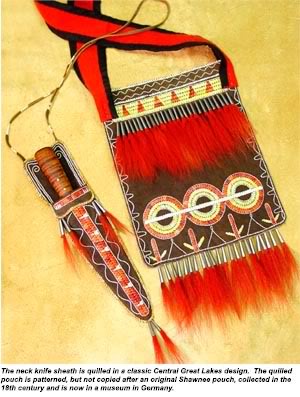

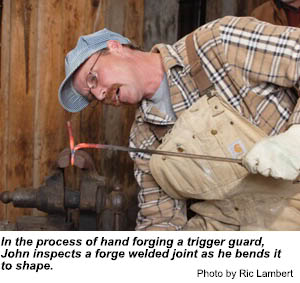

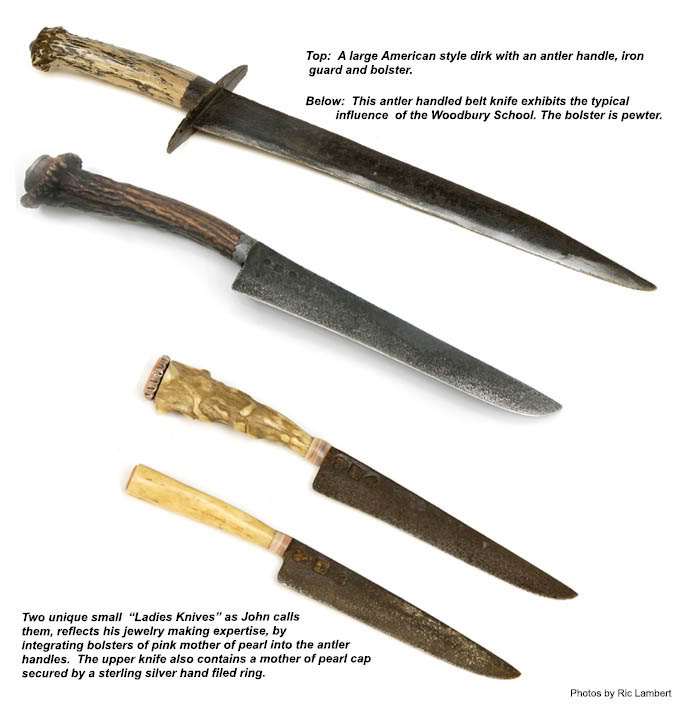

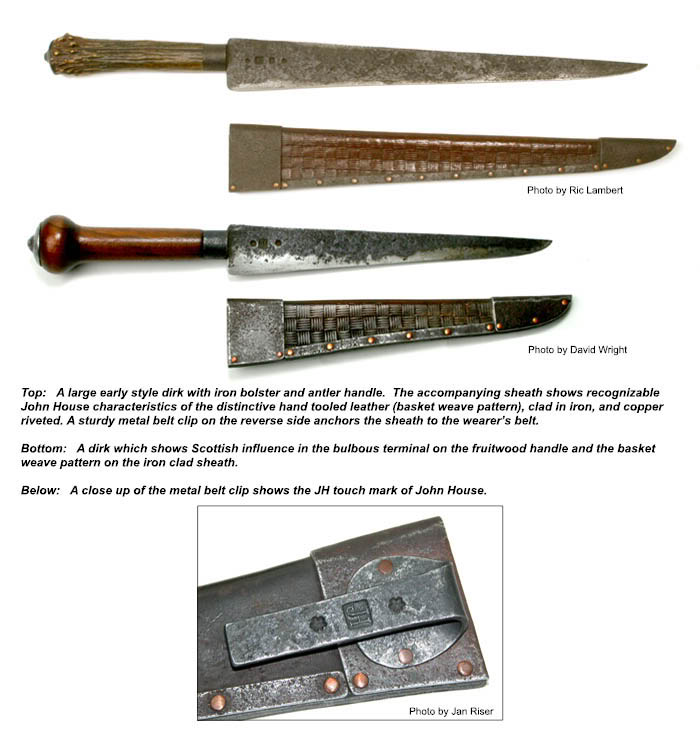

John’s gift and interests are first building knives, then longrifles. Over the years, John has built over 100 knives, including belt knives, dirks, and neck knives. In the beginning, buggy and truck springs were used, but today he prefers using 1084 or 1095 cutlery steal because it comes soft and can be shaped and tempered nicely. John says: “We always like to do French and Indian stuff. I like to beat the metal down close because that’s how they used to do it and that means leaving a little scale in order to come up with a good style. I have made belt knives, neck knives and daggers. A knife should have texture and character—I don’t like stuff that is too shiny. I also make my own knife sheaths. That way, the buyer can wear the knife right away and not just stick it in a drawer somewhere. I like to see my knives and guns used.” If you are looking for a historically correct longrifle or knife of heirloom quality, contact John by letter. Prices vary, but are reasonable considering the quality and historical accuracy of anything John builds. Be aware that John is an artisan who prefers to build from inspiration, so give him a general picture of what you are looking for and let him run with it—or he might even have a knife on hand you your liking! You won’t be disappointed.

If you are looking for a historically correct longrifle or knife of heirloom quality, contact John by letter. Prices vary, but are reasonable considering the quality and historical accuracy of anything John builds. Be aware that John is an artisan who prefers to build from inspiration, so give him a general picture of what you are looking for and let him run with it—or he might even have a knife on hand you your liking! You won’t be disappointed.

John’s Address is: PO Box 11 Woodbury, KY 42288

About The author:

Mark Sage fired his first muzzleloading rifle in 1979 and since then, the pursuit of understanding American history has been a one of the most powerful drivers in his life. He enjoys muzzleloading hunting, trekking, building firearms, powder horns and accoutrements. As an author and a public speaker on radio and television, he has spoken at a variety of venues about our early frontier history. Visit his website: www.portalsintimeinc.com